“My mother, the three-titted, six-fingered witch, the whore who fucked her brother and her minstrel. You look for her in the royal palaces, next time you’re there. See if her face hangs there. No. She is gone, taken from history as if she never was. And I, a prize to be married off for the best price, accused of whoring myself to Thomas Seymour! So valuable, as a virgin at least, to my brother or his keepers that what I want is as nothing.” The tears flow down her cheeks. “Bring him back, Guy Fletcher, so that just once, I can say quite what is in my head, in my heart. So that I can say to him, ‘Edward, I love you, it matters not who you are or who I am. Edward, I love you, the one who loves me despite that I am a princess, and not because of it. So that he can hear those words which I have thought so often and never said.”

Northampton turns to de Winter. “And you, Sir, who are you?” “George de Winter, My Lord. Son of the Baron of Sheffield.” “And I can count on your loyalty?” “You can. As you can count on my friend’s.” De Winter gestures at Longshawe. Northampton’s eyebrow rises. “I see. To whom do you report? Your father did not speak of you.” “I am in the service of Lady Mary, My Lord. She does not expect me to write a dispatch to her at every chance.” “So… the Protector’s man, and the heir to the throne’s man. Let us hope that we can work together.” It's not the first time I've commented on TV history. There's a particular approach that has become almost inescapable, one that is very easy to poke fun at and, apparently, one that programme-makers have no idea how to refresh. Professor Robert Bartlett would probably sit right at the centre of this archetype, walking dramatically through ruins at every opportunity, narrating in that almost Attenborough-ish way where there are more pauses than actual talking, showing us the odd document. The one of his that I watched recently (while ironing shirts for work, with the baby asleep - rock and roll all the way in my house) saw him repeat, several times over, the phrase 'it is said that...'. Hmm. Perhaps you didn't ought to find it a place in your relatively short script for the programme, then, because if it's only said that, rather than something to which you can give a bit more weight, the fact that it might be sensational isn't enough to merit inclusion. Ah, well. There isn't much in the way of written record for pre-Norman England, and it does make it hard to ground some of these claims. But his programme is (was? I think it's about ten years old, although it is currently being repeated on BBC 4) is interesting enough, and I will be watching the second and subsequent parts.

Susannah Lipscomb is a rather different prospect. She still does the things: the walking through ruins, the documents in those weird moving close-ups, the slow narration. But she does also get dressed up, and on this particular documentary, wades into a river to demonstrate the danger of wading into a river in Tudor-era woollen clothes. Which, it turns out, is remarkably dangerous. There's a sort of Nigella Lawson quality to her programme (Hidden Killers of the Tudor Home - a very sensible and low-key title...), a real sense that she, rather than the history she is relating, is the star of the show. I can't remember whether I made the same point relating to the Hannah Fry programme about whether maths is invented or discovered, but the programme makers have, frankly, fetishised the woman presenting it. In Fry's case, about 90% of the programme was sensible, her talking about maths, demonstrating, asking questions. 10% of it was ludicrously unnecessary shots of her prancing around formal gardens showing off her red hair. It seems that the people who made her programme also made Lipscomb's programme. 'These are women', they seem to have said, 'and, despite their intelligence, they also seem to look good on camera.' There was a meeting - readers of a certain age and set of cultural markers may have 'a strokey beard meeting' in their head - where it was agreed that instead of making (just) a serious maths or history programme with all the usual tropes, they'd make that and throw in a few of these additional 'but just look at her' bits. There's a bit of me that wonders how complicit the two women I've just mentioned are in their presentation as women. Then there's another bit of me that thinks exactly how awful what I've just written is. There's nothing I can usefully say about their choices, other than to hope for a world in which women on TV, presenting history, maths or science programmes, are not unusual enough for there to be this need to highlight difference. I suppose that it might be possible to level the same accusation at the people who make Brian Cox's TV programmes, because there is a definite 'look at him' element to them. These pieces are visual, and need to be watchable in that sense. Bartlett's Normans programme seems to achieve that by showing me a series of spectacular cathedrals and castles. Although, for some unknown reason, Bartlett seems to inhabit a sort of permanent winter, in which the sun is always low in the sky and he always needs a big coat on outside. For some reason, that seems to be our picture of the medieval period: no summers, only mud, fog, crows cawing. The Tudors, and no I don't know why, seem to be allowed to exist in the sun as well. In fact, I can't think of a Tudors documentary where the weather was miserable or obviously cold. I will obviously now be making the autumnal weather very prominent as the events of late 1549 take place... I can't even tell whether they belong in book IV yet. We'll see! Yes, we shall. These events are, approximately, at the same time as each other. The first extract is from the rising in the east, known as Kett's Rebellion, and the second is in the aftermath of the western rebellion, known as the Prayer Book Rebellion.

“Mary,” Longshawe says, “is not queen. Her beliefs are outlawed.” “Her beliefs,” de Winter counters, “are not to be challenged by her servants. God will recognise his own, when the time comes.” Andrew Shepherd holds out a hand, not pointing, but nevertheless confrontational. “As a child, I have not had the benefit of a priest or a tutor to guide me, or of books. I barely understand the Mass. But I feel God, and I know God. My sins are my own, as is my repentance.” He stands. “Your gear, Sirs, is in need of my attention. If I may?” Longshawe nods, while de Winter sits and stares at nothing in particular. Shepherd makes his way off into the crowd of assembled soldiery, his pretext sufficient if not clearly true. Longshawe turns to de Winter. “You should not be so hard on him. You said yourself, there are sins of which we do not speak. Your own sins. He is brave, to speak so openly before you.” “You are right. Of course, you are right. I shall try to protect him, rather than admonish him.” “Perhaps we can each learn from the failures of our fathers.” “And our own.” Thomas Gilbert looks up from his desk, attention caught by the slightest of sounds. In front of him, standing stock still and with his heels together, is Edward Strelley, dressed in black. “Jesus Christ, Strelley, can’t you just knock like a normal person?” “Didn’t need to,” Strelley says, looking straight ahead. “It must be ten o’clock.” “Just about. Dark outside. Not seen.” “Strelley, you are unusually terse. Explain.” “Need to escape. France, at least.” “Again? You didn’t get caught f-” Strelley’s sword is out of its scabbard and pointing at Gilbert’s throat. “Do not insult her.” “You are threatening me, Strelley. Just after you have asked for my help.” 800-odd years of history being destroyed by fire was sad. I described it in a previous post as 'utterly heartbreaking', which it probably didn't deserve, in retrospect. What was sad about the fire that damaged Notre-Dame was the fact that the world is just that little bit less rich than it was before, that humanity's size is somehow diminished as parts of its history are lost. It sounds as though the cathedral will be restored over the coming years to something approaching its true glory, which is a positive note to an otherwise unhappy story. But the cathedral church lives on in a sort of collective memory; those of us who have experienced it at first-hand share that experience, and whilst there is a difference, with the sorts of things modern technology is capable of, that experience can be closely recreated without ever being physically there. So, the loss is real, although less than seemed at first to be threatened. As you may note from the photos 'gracing' this website, I am partial to a ruin, although I would love to have seen Whitby Abbey at its peak, before even the time of my stories.

The news that upwards of 200 people have been killed in Sri Lanka in a series of attacks on churches and hotels is of a different type, and does deserve to be called utterly heartbreaking. The victims of these attacks were not combatants, and indeed in some cases they were worshippers. The parallel to the mosque attacks in New Zealand is fairly clear, in that a person or a group has planned to pick on a particular category of worshipper and cause as much death and damage as possible. Occasionally, I get angry, disappointed or sad, but I have not got a sense of what sort of illness of mind must obtain for that anger to come out in this kind of calculated way. There is a part of me that can understand the sort of anger that leads to the red mist that seems to underlie some instances of violent crime, even if I can't imagine actually committing those crimes. It's the main reason behind the extensive treatment of Edward Strelley's disappointment and anger about his frustrated love for Elizabeth. Strelley most certainly does imagine those crimes, and I leave it to the reader to find out by reading book IV whether he in fact commits them. I do not pretend to be able to write words of any real power or significance in response to a horrific series of crimes leaving over two hundred people dead and more than twice that many injured. Equally, I do not claim that my work in writing These Matters is somehow capable of explaining or giving insight into those crimes. But in writing the books, I have thought out - 'experienced' might be the right word, I'm not sure - that same anger and frustration that Strelley feels, and in him I can feel how it might channel itself into violence. Insight is not the same as justification, though. The people who committed the crimes in Sri Lanka have, perhaps, been failed by life, but that does not exonerate them. Their anger may have been justified, but their actions were not. What punishment ought to await them? I do not know, and I'm not sure it's of any value to speculate. It's a terrible question to answer if your maxim is 'be kind, regardless of the provocation'. It's impossible to quantify what goes into making a person who they are. It's almost trivial to say that it's a combination of heritage, upbringing, experiences managed and accidental, friends, teachers, family, relationships, everything that happens to someone might matter. But to pick out the things that will matter is beyond calculation, as any parent will attest. Things that seemed to matter at the time might have no lasting effect, whereas things that seemed irrelevant can be life-changing. The biggest thing for a parent, or indeed anyone trying to be a good influence on another person, is to act, not just to speak, in the right way. Sometimes, I manage to embody this, as when I picked up a lad who had done his best to hospitalise himself on the skate park this afternoon. He didn't, but it was definitely worth checking. Sometimes, I don't meet my own standards. And those are the things that go through my mind when I write about the sacrament of confession, because there's a bit of me that would like to be able to unload those failings on to a Priest and have God forgive me for them. Instead, I end up thinking of Keith Richards saying 'It's not just about living forever, Jackie. The trick is living with yourself forever.' Is there a message in any of this meandering? I suppose, that in addition to the core maxim of both Bill and Ted and Christianity (and pretty much all of the religions about which I might comment), 'be excellent to each other,' one ought to add: 'be excellent to yourself'. Only with both can anyone be at ease in the world. I thought about writing 'only with both can anyone be happy', but perhaps 'happy' is asking too much. It's easy to dismiss middle-class white folk who say 'Peace!' as a greeting or farewell, but perhaps it ought to be what we say to each other. So: peace be with you, whatever life you lead, and whatever your beliefs. I basically refuse to look at the photos, the video, the aftermath of that fire. As a much smaller person, I visited the Catholic cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. I can't really remember what it was like inside, but I do have a very vivid memory of being impressed by the rose windows. I've visited Paris again since, including one rather memorable (better: 'notable'; 'memorable' definitely gets one aspect of that weekend wrong) visit which, through a series of predictable-but-not-entirely-my-fault circumstances involved me trying to negotiate my way into my own hotel room to retrieve my mobile phone, to discover something in the range of sixty calls and text messages. I opened in French. The bloke on the counter did not let me get far massacring his language, and somehow I managed to get in, get my phone, establish that the person I had told to wait for me was so enraptured with his ice-cream that he wasn't even aware I had spoken to him, and catch up with them in the Tuileries. Of a very different era but equally iconic, I suppose, I went up one of the World Trade Towers a couple of years before they were destroyed by terrorists. The significance of my visits has been increased by subsequent events.

That palace, the Tuileries, was destroyed by fire in 1871 (yes, I did have to look that up and check). It's hard at this remove to imagine the gardens in their original state, with the enormous building no longer there. In a similar vein, the St Paul's I write about in These Matters is not the one that we are now familiar with, and I occasionally find myself having to look up paintings or checking details online. That drive for historical accuracy is fuelled in part by the very ease of access to information. If I can look it up, so can my readers. And if they're picking up a historical novel, the chances are high that they will have some investment in it being accurate or at the very least consistent with the real history. That places a high demand on me as a writer, because, unlike Dumas, I can't so easily bend timelines or places to suit my narrative. What I have been concentrating on in book IV is the sense of truth-to-life of the characters, in terms of what their lives were (and, inevitably, the influence of religion in their day-to-day existence as well as on the big events) and how they react to events. Things that I didn't know about them have come out, situations that weren't there in the original plan. In a way, that's part of the fun, to channel these imagined people into existence. Even the historical characters reveal things about themselves through this process, although that is where any claim to strict authenticity has to fail. Strelley and Elizabeth is a sort of theory, a candidate explanation for how she was later in her life. But it cannot be the real truth, except by an astronomically unlikely accident of chance. As a writer, I suppose the goal is to write something 'true' in a very different sense, believable and authentic, regardless of strict accuracy. Mary Stuart did not have a Hallamshire gamekeeper for a guardian in her early childhood, but it makes a good story. I wonder what Pike will make of Notre-Dame... Most of this post was written on a mobile phone. Dodgy spelling or otherwise nonsense to be blamed thereon! Yikes. Really interesting from Billy Vunipola to say that there's no hate, there's no lack of like or love for those people he marks out as the future inhabitants of hell. It comes, no doubt, from a sense of love for his fellow human being and that love manifests itself as this warning against sin. Of all the things that Jesus doesn't seem to be into, though, there's huge significance in the injunction against judging others. Let him, we are are told, without sin cast the first stone. Since no one is without sin, other than perhaps Jesus Himself, no one has that right. One can't help but feel that Jesus would be disappointed that the core message, of love for one's fellow human being, is lost by those who think they are embodying that cause. As Father Harper says to Edward Strelley, the God of the New Testament, his mouthpiece in the form of Jesus, is not vengeful, not angry. He is, as we are taught, Love. And that love is not embodied in condemnation of other people's sins. Seeing the whole Bible as the word of God is to miss its essential historicity, its existence as a set of documents chosen, edited, manipulated and translated by men. The Bible is a fascinating document, partly because of this context. The argument that it is somehow a perfect document is more-or-less impossible to refute by conventional means, because it is one of those self-defending lines of reasoning that is immune to any of the methods you might use to attack it. The involvement of people, it is supposed, is neither here nor there in establishing the divinity of the words, because the divinity is there despite the involvement of people. The choices they made are divinely inspired. And so it goes.

The quotation on the landing page at the moment is from Fleabag. Not something that I've watched with any great engagement, although it is clearly a well-written and inspired comedy. Andrew Scott (the bloke who played / plays Moriarty in the Benedict Cumberbatch Sherlock) delivers this heartbreaking speech at a wedding, searching for a way to add something to the canon of things to be said about love. The context is that he, as an avowedly celibate Catholic priest, is not permitted to act on the love that he feels for the main character. Even written down, it carries some of the brilliance of the scene. But I would recommend to anyone reading this who can get access to it watch that scene, even in isolation from the build-up. It's not that often that I am jealous of someone else's writing. But in this case, Phoebe Waller-Bridge has it spot on. As good as anything in The History Boys. "It'll pass," he says to her afterwards, choosing God, his vocation - what is right, in his mind - over his love for her. But, as Posner says, "who says I want it to pass?" I've (already) spent years trying to capture that 'how it essentially was' on the page. I don't think I'll give up just yet, but I'm not sure I'll ever quite get there. The strange interregnum of 'between cars' is a borderline frightening throwback to a time of my youth when the way of getting about the place was the number 97 bus into town, and possibly a SuperTram to Meadowhall. It was rock'n'roll all the way. Now, bereft of the freedom to just jump into the car and go wherever, I have had to recalibrate everything around the challenges of getting to and from work and making sure there is adequate food in the house without just turning the key and driving off. Those of you who know me may well be aware that any time before eight in the morning is unlikely to find me in a sociable mood. I used to get around this problem in London by having a book (this is in the days before internet-enabled smart phones, of course), my particular favourites being the late Victorian duodecimos that can, with patience, be read and page-turned one handed. That leaves the other hand free for stiff-arm fending the other commuters when they get too close. More recently I have travelled to and from work in the glorious isolation of the car, with nothing other than Today or the Infinite Monkey Cage for company. So it is somewhat of a stress to have to be socially presentable when sharing a lift, particularly in the morning. I hope my lift partner has found my company acceptable, as it is probably even more of a challenge to let someone sit in your passenger seat and distract you from your choice of radio than it is to be that passenger.

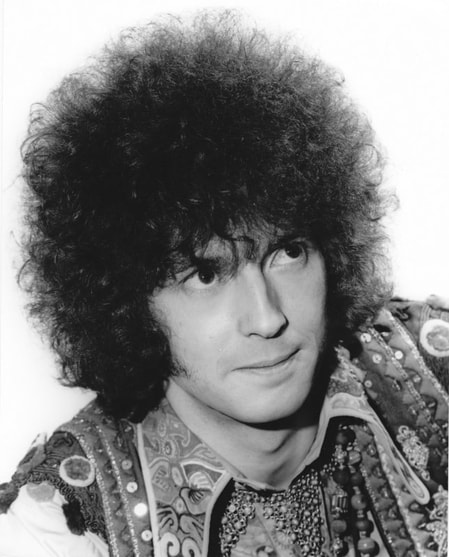

A sort of nod-cum-toast, then, to freedom. Not the kind that rings with a shotgun blast, but the quiet, peaceful kind that comes with being able to choose. Not wheels, and an engine, and pedals. That's what a car needs. But what a car is, what a car really is... is freedom.  The smallest Richardson earlier today... The smallest Richardson earlier today... Not since the bit when Caligula has Gemellus killed for his persistent cough has there been quite so annoying a bark as the ones currently to be heard at home. It's a bit of a design flaw, I think, in the human body, that an illness of relatively minor proportions is capable of causing such a distressing noise. Thomas Mann takes great pleasure in describing a cough in the early part of The Magic Mountain; I do not take any such pleasure in experiencing it. And of course since I started writing this post (two whole days ago, early Friday evening) I am now afflicted with the same rasping, barking cough as previously I was subjected to only as a bystander. It is worth saying two things: the first is that cough mixture does not work, which is a disappointment. The second is that the disturbed sleep of the cougher and the coughee mean that all manner of people are short tempered and irritable. Not exactly the best environment for creativity, although it does provide plenty of ideas for a lightly humorous blog post. Owning a child is a sort of custiodianship, akin to stacking the shelves and putting the stuff back where it belongs in the supermarket. Except that the supermarket has been overrun by small, chaos-aligned midget drunkards with a real desire to change all the gravitational potential energy in the universe into something less ordered. A kind of entropy-increasing second-law-of-thermodynamics-proving machine that exists to test the patience of parents everywhere. What is especially fascinating and ultimately disheartening about this is that the tidying-up-at-the-end-of-the-day process actually increases the overall disorder of the universe, even if it reduces the local disorder. Some children are builders, apparently, although those ones would have to outnumber the wreck-smashers by a good three hundred to one before any actual built thing would have a chance of even fifteen minutes of survival, as the process of destruction is vastly quicker than the process of construction. My own really tiny human is very much of this cast of mind, seeing anything vertical as a challenge. Either he wants to knock it over, or he wants to go up it, and given his lack of gross motor skills, the inevitable rapid return to ground level follows, although so far no trauma-related trip to the Children's Hospital. Whilst lacking any kind of long-range coordination, he does have a remarkable ability to notice if there is better (or just different) food anywhere in the room. As a result of this, his loud and penetrating voice (I've no idea where this came from, by the way) and his sheer persistence in shouting, he ended up testing a crinkle-cut salt and vinegar crisp today. I'm not sure whether he liked it, but the look of triumph on his face when he finally got it was a sight to behold. He has also learned to issue instructions, limited in scope (mostly to providing more and better food), but nevertheless clearly intelligible. His latest wheeze is to point at the TV and shout something that begins with a 't', which translates as 'I want Thomas the Tank Engine. Now!' Weirdly, the episodes on his DVD are ones that I must have had on a video tape when I was little, because some of the bits Ringo Starr (yes, that Ringo Starr) narrates are etched deep into my person. It's not like that memory is there, present to my mind, but when Gordon starts moaning, I know both what he is going to say and how he is going to say it. Much as, watching Back to the Future with the bigger one, I know exactly how Doc Brown says '1.21 gigawatts'. What I did not remember is how much they swear in that film. But she has now crossed over the line from being mortally offended to finding swearing funny. Which, for the most part, it is. Except when it's a test, a way of finding out if you've ceased to be a teacher and become a friend (couldn't resist the HB quotation...). I wonder what mine will remember when they are older. Will the Sesame Street songs bring back a strange flood of child-ness, I wonder? I made the mistake of clicking on a video of Robin Williams trying to explain conflict to the two-headed monster. Yes, tears yet again, confusing the small one no end, I think. And that just from the sight of him. Robin Williams, that is, not the two-headed monster. Or, for that matter, the tiny one's ludicrous unaerodynamic hair. “Strelley?” he asks. Then he confirms by repeating, “Strelley.”

Edward Strelley says nothing. Instead, he bows his head, and his eyes close in silent prayer. “I had not thought to see you again,” Harper says. “But I am glad that you have come.” Again, Strelley says nothing. Harper goes to him, and takes his hand. “You have not seen your fellow man at his best since we last spoke. Do not be disappointed. God will love them all just the same. I am sure of it.” “The sinners? The unrepentant? The unfaithful?” Strelley’s voice is cracked and uneven. “Yes, Edward. He loves them.” “But He does not take them to Him in Heaven.” “Ah, you presume. I do not pretend to know the mind of God. But if Hell is anything, it is to be apart from God. Not some fiery torture, for that is nothing compared to being without God.” “The suicides?” “Do you think, Edward Strelley, that God is vengeful and angry?” Strelley lifts his eyes to Harper’s. “The God of the Old Testament is.” “God, who sent us His son to save us from our sins? Do you think that God, who can see through the masks and the words of men, for whom a life such as ours is no more than the blink of an eyelid, do you think that such a God could abandon his flock, no matter their sins?” “We are taught that we must avoid sin. Repent.” Harper smiles. “That you must. But if you fail God, He will not fail you.” |

Andy RichardsonWhen to the sessions of sweet silent thought Archives

March 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed